The producer consumer pattern can be “easily” implemented in Java using one of the BlockingQueue classes. The producer puts work into the queue and consumer takes work from the queue. We start two separate threads for the producer and consumer. After that we just have to wait for the threads to complete. How do we do that? You might think of starting with this:

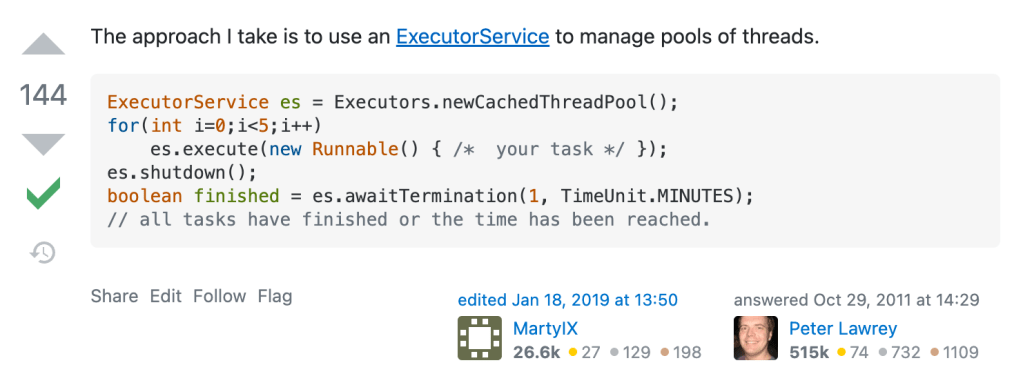

Just replace the Runnable with your producer and consumer. This answer has been vetted by SO and has a whopping 144 votes. What could go wrong? Well, this code works fine as long as we stick to the happy path. By happy path I mean the situation when there are no runtime exceptions. Things happen as expected.

But think for a moment what will this code do when the unhappy path is encountered – as it often happens not during local testing but when code is deployed to production. Imagine the producer (thread) crashes interim. The consumer (thread) will keep on waiting indefinitely because it doesn’t know the producer has crashed and it is waiting for the final message from producer to signal there is no more work to be done. The call to es.awaitTermination will never return (assuming your timeout was infinite). Yes, that is how ugly it can get. The awaitTermination blocks until all tasks have completed execution after a shutdown request, or the timeout occurs, or the current thread is interrupted, whichever happens first. Remember that if an exception happens in the consumer, it is not the same as an exception happening in the thread that runs awaitTermination.

You might think if awaitTermination could be somehow modified so that it blocks until all tasks have completed execution after a shutdown request, or the timeout occurs, or any task encounters an unhandled exception, whichever happens first. That might solve it. No, it won’t. Want to know why? In that case, when the consumer crashes, the call to awaitTermination will return and let’s say your main thread exits. In Java, your program can keep on running even if the main thread has exited! So the consumer thread still keeps running waiting indefinitely for work to arrive from the producer and keeps your program alive.

These are not some artificially concocted cases. They are pathological for sure but I have seen them happen first-hand. The difficulty in implementing the producer consumer pattern involves handling all these exceptional cases properly. What should we do if consumer crashes? What if producer crashes?

There are so many ways to get it wrong that I will just give the final answer on how to do it right. In below Work will be a class that you will write which encapsulates the work to do. When a consumer receives Work.EMPTY that tells the consumer there is no more work to be done. We make use of a ArrayBlockingQueue which takes a lot of the pain away in implementing the producer-consumer pattern. It is the very heart and soul of the producer consumer pattern. We only create a single producer and a single consumer in the code below but think how will you modify it if you have 100 producers and 100 consumers.

private static Throwable waitAny(CompletableFuture<?>... cfs) {

try {

CompletableFuture.anyOf(cfs).join();

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

return e;

}

return null;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

BlockingQueue<Work> sharedQueue = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(10);

Producer producer = new Producer(sharedQueue, producerArgs);

Consumer producer = new Consumer(sharedQueue, consumerArgs);

ExecutorService es = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

CompletableFuture<?>[] futures = new CompletableFuture<?>[2];

CompletableFuture<?> producerTask = CompletableFuture.runAsync(producer, es);

CompletableFuture<?> consumerTask = CompletableFuture.runAsync(consumer, es);

futures[0] = producerTask;

futures[1] = consumerTask;

Throwable t = waitAny(futures); // wait until one of the tasks completes

if (producerTask.isDone()) {

if (producerTask.isCompletedExceptionally()) { // Returns true if this CompletableFuture completed

// exceptionally, in any way. This includes cancellation

// of the task.

// unhappy path

// we want to wait for consumer to finish

// consumer will not finish until it gets an empty Work

if (!consumerTask.isDone()) {

sharedQueue.put(Work.EMPTY);

}

}

consumerTask.get(); // wait for consumer to finish

} else {

// in this case the consumer finished first

assert consumerTask.isDone();

if (consumerTask.isCompletedExceptionally()) {

// unhappy code path

// if consumer has failed, no point in letting the producer run

// if we don't cancel the producer, it will keep waiting indefinitely

// for sharedQueue to become available so it can queue more work for the consumer

// (the producer does not know that the consumer has crashed)

producerTask.cancel(true);

}

producerTask.get(); // wait for producer to finish

}

if (t != null) {

// do you understand why we need to do this?

System.exit(1);

}

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

// without this, the program can still keep running even though main thread has

// exited. Its Java.

System.exit(1);

}

}

Your producer and consumer classes should implement the Runnable interface. e.g.:

class Consumer implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

}

}

In the run method you will call the put and take methods of BlockingQueue (producer calls put to put Work into the queue and consumer calls take to take Work from the queue) that can throw the checked InterruptedException. Do not swallow the exception! Re-throw it.

class Consumer implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

try {

...

} catch (InterrupedException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

}

And that’s how I learned to do it right. This post does not detail all the mistakes and hundreds of ways I did it wrong before arriving on the correct solution. Believe me, it was hard to get this right. And it would be 10x harder if we did not have the BlockingQueue class. Once again, most of the time we only test the happy path (as exemplified in the SO answer at beginning of the post) and thus never discover the hidden flaws in our code. I urge you to try the unhappy path in your software applications and see for yourself if your code can handle it.

UPDATE (2022/08/11): Even the code above has a bug undesirable behavior as I found out later. It is this: the main thread exists but the program still keeps running for a minute in an idle state before finally exiting. Upon investigation I found it is because of the 60s default keep-alive time of newCachedThreadPool. To fix this one should substitute the call to newCachedThreadPool with newFixedThreadPool(2) and also one should not forget to shutdown the ExecutorService otherwise the program will keep running forever.